From whispering forest spirits to fertility tricksters and siesta‑time child snatchers. Guaraní mythology is one of South America’s richest oral traditions. Though reshaped across centuries, and often filtered through European imperial interpretation, these stories still pulse through Paraguayan popular culture, art, and rural imagination.

For newcomers trying to understand Paraguay beyond first impressions, entering the world of Guaraní belief is like learning the emotional language of the land.

Oral tradition, European writing

Before European contact, the Guaraní – Paraguay’s indigenous people – transmitted knowledge orally: through song, prayer‑poetry (ñe’ẽ porã), initiation chants, and storytelling by the fire. No widely used native alphabetic writing system fixed these tales.

When the Spanish Crown and Catholic orders, notably the Jesuits, founded missions (reducciones) from the 16th century onward, missionaries began recording language and belief to translate doctrine, teach catechism, and administer communities. Much of what survives in writing today as “Guaraní mythology” comes from those vocabularies, confessional manuals, homiletic notes, and, later, clerical or traveller compilations.

Spirits were likened to demons, culture heroes to saints; fertility figures became morality tales. Meanings shifted. In the 20th century, researchers such as León Cadogan, Branislava Sušnik, Bartomeu Melià, and José María Blanch worked with Indigenous informants to document versions closer to community memory, but gaps remain. Every written account, including this one, is an approximation shaped by translation, time and power.

The seven legendary brothers

Among the best‑known figures in Guaraní mythology are the seven sons of Tau (a malevolent forest force) and Keraná, a mortal woman. Cursed into monstrous forms, each son is linked to a realm of nature, behaviour or taboo. Versions vary; these are the traits most told in Paraguay today.

Teju Jagua: A giant lizard (or iguana) with a dog’s head, sometimes six ember‑bright eyes. Slow, scale‑armoured, keeper of caves and rocky hills. Said to guard hidden stones or burials, he punishes greed and reckless digging. Children hear: do not disappear into pits or quarries without elders.

Mbói Tu’í: A great serpent with a parrot’s beaked, feathered head. Damp, river‑slick coils; a hiss like distant bird calls. Protector of marshes, and wetland life. Pollute the water, or mock the swamp? And illness or storms may follow. Parents warn do not swim alone in weedy backwaters… the parrot snake watches.

Moñái: Shown as a long-horned snake or shaggy, long‑armed being tangled in creepers. Master of open country and horizons. He confuses travellers, bends distance, steals unattended tools. Farmers mark their paths, and put gear away “so Moñái does not misplace it”.

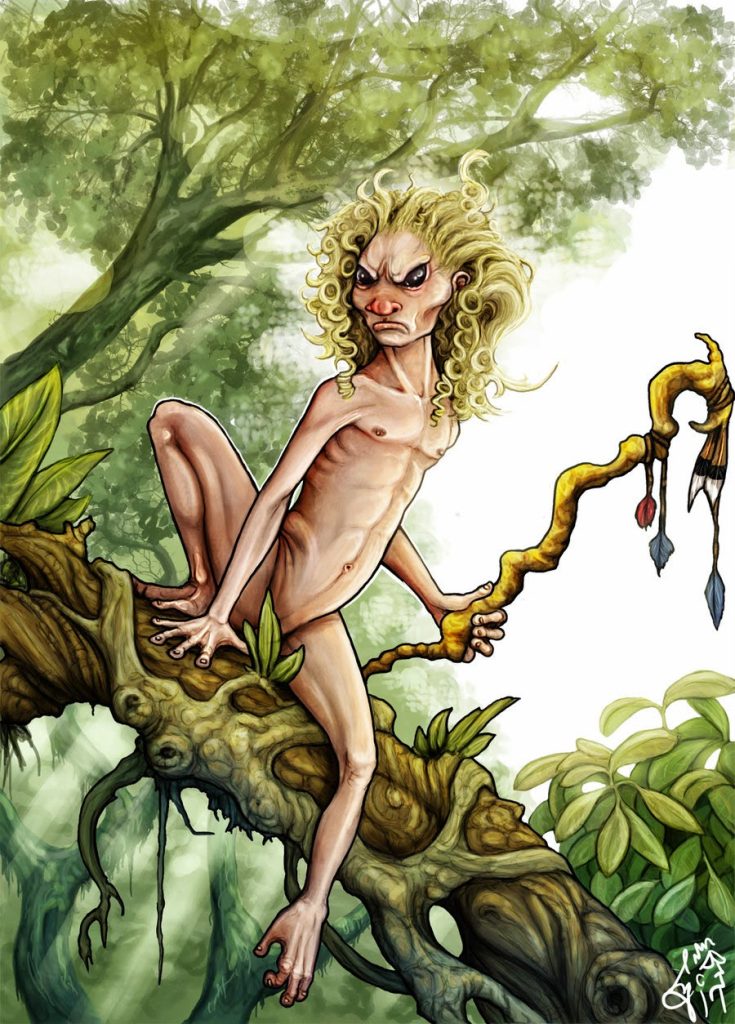

Jasy Jatere: The only fair one of the seven sons: child‑like, golden‑haired (or luminous), carrying a sugarcane wand. Walks at midday, guardian of the siesta. Obedient children nap, wanderers may be led off with fruit and play. In stern tellings he blinds or bewilders; in gentler ones he protects lost youngsters until found.

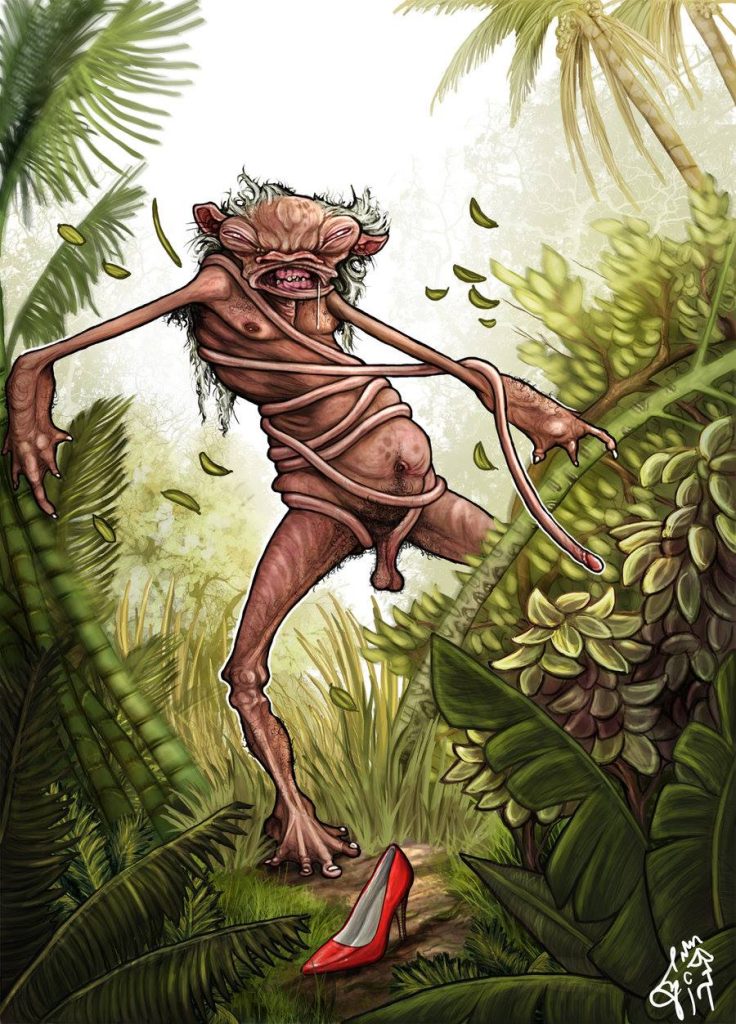

Kurupi: A recognised icon

Kurupi: Small, dark, wiry, with an absurdly long prehensile phallus looped like a belt. He is the embodiment of untamed sexuality and fertility. Long used in folklore – and in mission times – to explain secret or forced pregnancies, when shame silenced the truth. Rural warnings: avoid lonely paths at night, Kurupi prowls the thickets… Nowadays Kurupi is also a renowned Paraguayan brand of yerba mate, the traditional cold-brewed drink.

Ao Ao: A woolly, horned sheep‑beast that hunts in packs, bleating as it charges. Pursues those who steal food, insult elders, or waste the land. Escape by climbing a pindó palm, Ao Ao cannot grip the smooth trunk. Lesson: respect family and food stores; value palm groves.

Luisón: Gaunt, long‑haired, man‑dog creature of night, strongest (some say) on Tuesdays and Fridays. Fetid odour; cemetery wanderer. Harbinger of death and decay; a warning to care for the sick, honour burials, and keep ritual hygiene.

What about “Pombero” then?

Not one of the seven brothers, yet Paraguay’s most famous forest spirit is Pombero. Small, hairy, long‑armed, fond of tobacco, honey and mischief. Unties livestock, braids horses’ manes, steals eggs, mimics birds. Many families still leave offerings on fence posts por las dudas; just in case…

References surface everywhere: children’s books, mural art, San Juan winter fair games, school ecology talks, Pombero graffiti, brand labels. Legal and conservation advocates sometimes invoke Guaraní cosmology when arguing to protect sacred forest or water sites. The mythology lives because it adapts.

Understanding Guaraní worldview

Guaraní mythology is not a fossil of “old stories”, but a living symbolic toolkit: teaching respect for nature, warning against excess, encoding social rules and holding room for mystery. Filtered, translated, retold, yet persistent. Listen for these beings in rural jokes, festival songs and place‑names, and you will hear how deeply they still root Paraguay to its Indigenous soul.