Dr Martín Almada, a distinguished Paraguayan human rights lawyer, educator, multiple award winner, and co-founder of the ‘Museo de las Memorias’ (Museum of Memories) in Asunción, passed away on 30th March at the age of 87.

He leaves behind a monumental legacy of standing up to repressive military regimes, with his work impacting the lives of millions across South America.

Almada received several awards for his courage and work, including the prize “Antorcha a la libertad” (“Torch of Freedom”) from the Libre Foundation in Asunción in 1999, and the Right Livelihood Award in 2002.

Born in 1937 to a low-income family in Puerto Sastre, a small rural area of northern Paraguay next to the border with Brazil, he moved with his family to San Lorenzo, just outside of the capital Asunción, when he was six years old. His parents found work in factories and small shops, and Martín sold pastries on the street to help bring in extra money.

He graduated from the National Academy of Agronomy with a degree in education in 1963 and in addition to working as a classroom teacher, he founded the Juan Bautista Alberdi Educational Institute in San Lorenzo – originally an Academy, which later expanded to primary, secondary, and technical education – along with his wife, Professor Celestina Pérez de Almada. The educational institute they founded outlives both of them, and continues to educate young Paraguayans today.

Martín then embarked on a law degree, graduating from the National University of Asunción in 1968. He was known locally for taking on pro bono legal work, including helping poor villagers and farmers with housing and land rights issues.

He obtained his PhD in educational science at the University of La Plata in Argentina, graduating in 1974. His doctoral thesis, entitled “Paraguay, education and dependency” – later revealed to have been passed to the Paraguayan government as part of CIA-backed Operation Condor – saw him branded as an “intellectual terrorist” by the military authorities under the rule of Paraguayan dictator Alfredo Stroessner.

After being imprisoned in 1974, he was held as a political prisoner for around three and a half years, during which time he was repeatedly tortured, almost to the point of death. His wife, herself under house arrest, was forced to listen over the telephone to her husband’s cries as he was tortured. At one point, the police falsely told her that her husband had died, and gave her a loincloth covered in blood, along with masonry nails they said were used to remove his fingernails. She then had a heart attack, and died.

Dr Almada was eventually released in 1977, after a campaign by Amnesty International. Almada himself credited several organisations with supporting the effort: the Committee of Churches of Paraguay, the Human Rights Commission of Paraguay, the Episcopal Conference of Paraguay and the World Council of Churches.

Upon being released, Almada fled to Panama, where he was granted asylum. along with his mother and his children, and wrote the book entitled “Paraguay: The Forgotten Prison, The Country In Exile”, in which he details the torture suffered by himself and others at the hands of the Stroessner dictatorship.

He later moved to Paris, France, and in 1986 began working for UNESCO. This continued up until 1992, when he decided to return to Paraguay – a decision which would have ramifications far beyond Paraguay’s borders.

“I returned to Asunción, went to the courts and asked to be given the right of access to my files,” he recounted. “And the police replied, ‘There were no files’ because [officially] I had never been in prison.”

Then in late 1992, he received a visit from the disgruntled wife of a former regime bodyguard. “Her husband drank a lot and went with other women,” he told the Miami Herald. “She really hated him.” She gave Dr. Almada a tip: She knew some records were kept at a police station in Lambaré, a town near Asunción. Maybe it was worth looking there.

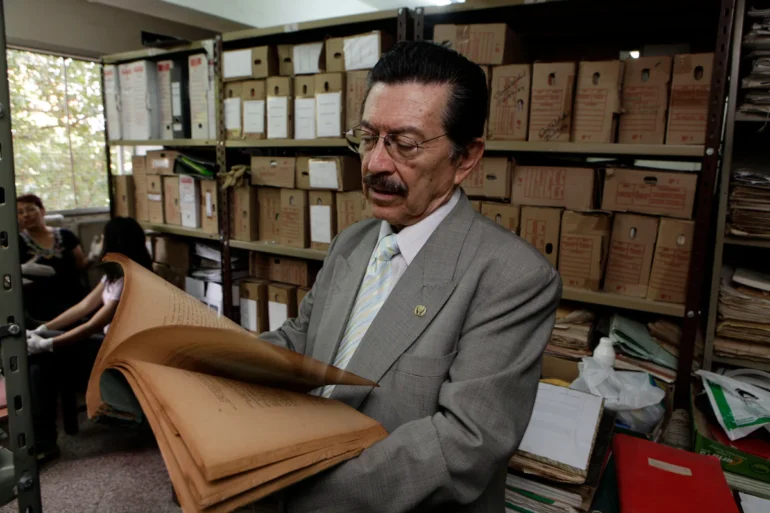

So on December 22 1992, Dr Almada, along with Judge José Agustín Fernández, went to visit the police station in Lambaré, hoping to find something which might lead them on to another line of inquiry.

Instead, they found archives meticulously detailing the kidnap, imprisonment, torture, and death of nearly 500,000 Latin Americans at the hands of state security services under the military dictatorships of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay – all with the support of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from the United States of America.

This collaboration of evil would go on to be known as “Operation Condor”; the files discovered by Dr Almada and Judge Fernández that proved the existence of it would come to be known as the “Archives of Terror”.

“I felt that each folder we opened up would help us go back to the past and understand the regime of terror which we suffered,” Dr. Almada told the BBC in 2002. “Every document revealed terror and tragedy.”

In total, the “terror archives” listed 400,000 people who were imprisoned, 50,000 who were murdered, and 30,000 who were “disappeared”, as well as detailing meetings held by the intelligence services of the involved countries, which also implicated Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela.

Alongside a total of 60,000 documents, weighing 4 tons and comprising 593,000 microfilmed pages, Almada also found the tape recordings of his own torture.

The evidence contained in the archives would go on to be used against some of the perpetrators in court, notably former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, one of the original founders of Operation Condor.

Prosecutions related to Operation Condor continue to this day. As recently as 20th February 2024, a former police officer under the Stroessner regime was convicted of torturing his fellow Paraguayans and sentenced to 30 years imprisonment, in a trial held at a courthouse at Asunción’s Palace of Justice – also home to the Supreme Court of Paraguay.

After years of campaigning by Almada, the ‘Archives of Terror’ were finally added to UNESCO’s “Memory of the World Register” in 2009, at the same time as Cambodia’s Toul Sleng Genocide Museum Archives.

Today, the archives unexpectedly discovered by Dr Martín Almada are collected and organised in their own room, on the eighth floor of the same building which continues to hold trials related to the information they contain – Asunción’s Palace of Justice.

In 2002, Dr. Almada recounted to the BBC how he kept his hopes and morale up during his imprisonment, fighting back in the only way that he could – with his words to the prison guards who tortured him.

“When I was handcuffed and shackled, I used to say to them that the world was a slowly turning wheel, and that sooner or later democracy would come and I would play a very important role,” he said. “I made that up, of course, and I doubt they believed me, but in a way, it has.”

Such an introspective look! The history serves us as a warning