Paraguay’s currency offers a window into the country’s past, tracing the path from the earliest systems of trade to the structured economy of the present. In “Money Talks”, The Asunción Times examines the milestones that shaped the guaraní, revealing how each denomination reflects moments of transformation, and national identity. The series explores the imagery, symbolism, and decisions that defined the nation’s monetary landscape. In this seventh, and final episode, we revisit the Gs. 1,000, tracing its journey from an early banknote, to the enduring coin that people in the country carry today.

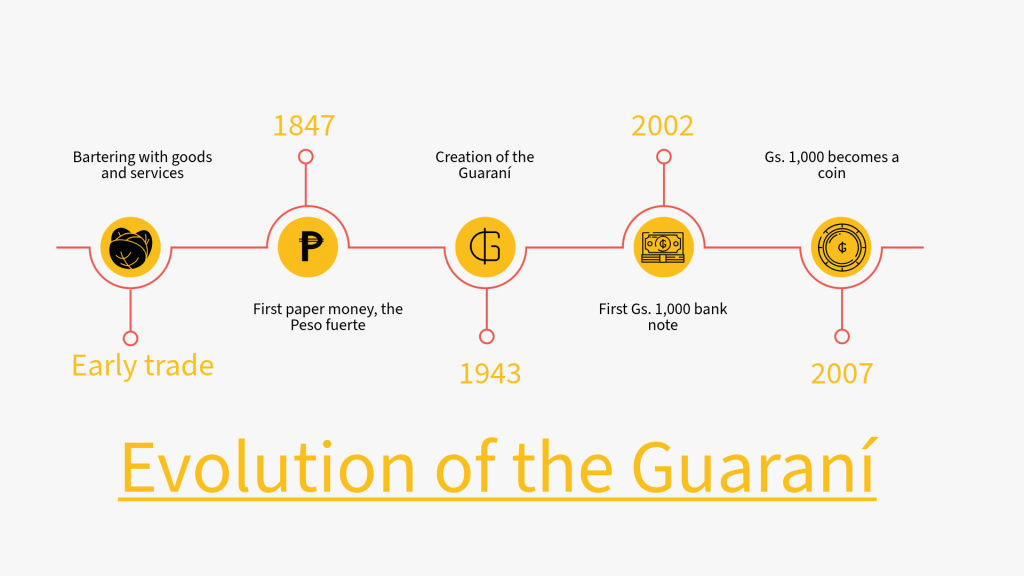

After uncovering the iconic mix-up on the Gs. 2,000 note, the hidden design elements of the Gs. 5,000, the disputed iconographic detail of the Gs. 10,000, the artistic legacy behind the Gs. 20,000, the three intertwined stories of the four versions of the Gs. 50,000, and the attempts to remove three zeroes from the Gs. 100,000 note; this chapter turns to an origin story. It follows the evolution from barter to the peso fuerte, the decisive creation of the guaraní in 1943, and the development of one of the most recognisable values in circulation.

Before coins: An economy built on barter

Before Paraguay had a formal currency, most exchanges relied on barter. Yerba mate, tobacco, cattle, cotton cloth, sugar, and other agricultural goods acted as units of value. These products were widely accepted across communities, and easier to access than precious metals, which were scarce in the region.

Spanish coins such as pesos, reales, and cuartillos circulated but were limited. Paraguay’s isolation made consistent minting difficult, and the country depended on foreign currencies that were often countermarked or cut into pieces to suit small transactions. This system created an inconsistent and fragmented monetary environment.

First attempts at national currency

A more organised system began in 1842 when Carlos Antonio López authorised the minting of Paraguayan coins. These early issues helped define a national identity, but shortages of metal persisted. In 1847, the government issued its first paper money to stabilise trade, and reduce reliance on imported coins. The experiment was short-lived, because the War of the Triple Alliance destroyed much of the early system.

In the decades that followed, a mix of foreign and altered coins remained in circulation. By the late nineteenth century, the peso fuerte became Paraguay’s principal currency. It provided more stability than earlier systems, and became the base for official payments and state accounting.

The rise and limits of the Peso Fuerte

Although the peso fuerte offered greater structure, it gradually weakened in the early twentieth century. Fiscal pressures, inflation, and the absence of modern financial institutions limited its capacity to support long-term growth. Paraguay required a currency that could promote stability and reflect a modernising nation.

This change came on 24 November 1943, when Decree-Law No. 18.746 established the guaraní. One guaraní equalled one hundred pesos fuertes, removing two zeros and introducing a more coherent monetary framework. The reform aimed to simplify accounting, stabilise prices, and support a stronger financial system.

The birth of the Guaraní

The choice of the name “guaraní” held symbolic weight. It rejected colonial terminology and embraced indigenous heritage as a defining element of national identity. This cultural dimension accompanied broader administrative reforms, including the later establishment of Paraguay’s Central Bank (Banco Central de Paraguay, or BCP) in 1952.

The first guaraní banknotes, issued in the mid-1940s, ranged from 1 to 500 guaraníes. As the country expanded economically, new denominations were added, including the 1,000-guaraní note that soon became one of the most familiar values in circulation.

Early banknotes, and the formation of a national identity

The early 1,000-guaraní note incorporated patriotic imagery. It displayed Marshal Francisco Solano López, the national coat of arms, and central depictions of the Church of the Virgin of the Assumption and the National Pantheon of Heroes. These symbols reinforced a unified, historic narrative during a period when Paraguay sought institutional and economic stability.

In 2002, a commemorative edition honoured the fiftieth anniversary of the Central Bank, highlighting the denomination’s importance in daily life.

The Modern Transition

By the late twentieth century, lower denominations began shifting from paper to metal, as coins were more durable and cost-effective. The Gs. 1,000 note, used constantly in everyday transactions, became a natural candidate for replacement.

In 2007 the Gs. 1,000 coin entered circulation. By 2009 the banknote was no longer printed and was officially demonetised. The transition mirrored global trends where frequently used values move to coins to reduce long-term production costs.

A collector’s item and a reflection of monetary change

Today, original Gs. 1,000 banknotes survive mainly as collector’s pieces. Depending on condition and rarity, some are worth many times their original value. Their transformation from daily currency to numismatic object reflects Paraguay’s wider monetary evolution.

From barter to the guaraní, Paraguay’s currency has travelled a long path towards stability and national identity. The story of the Gs. 1,000-once a defining banknote, now a durable coin – captures this process of adaptation, and economic modernisation.