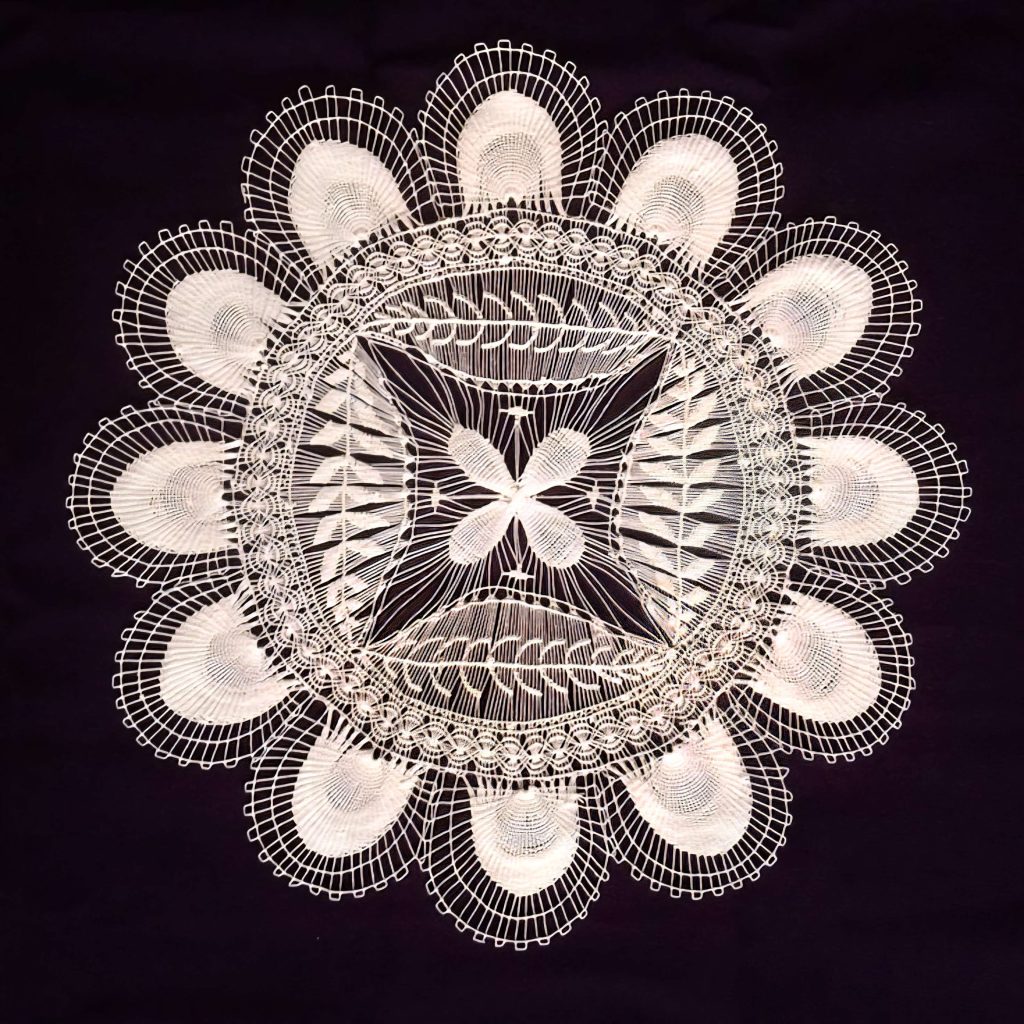

Ñandutí, whose name in Guaraní means “spider’s web,” is much more than delicate lacework: it embodies mestizo creativity, historical memory, and Paraguay’s cultural identity. Every year, on the second Sunday of October, Paraguay celebrates National Ñandutí Day, honouring this lace as the “queen” of national handicrafts and the hallmark of the city of Itauguá. This needle lace has reached international showcases thanks to its exquisite beauty and the deep stories it preserves.

An art born from two worlds

Ñandutí is the product of a cultural encounter. Rather than being exclusively indigenous, it combines European needle-lace techniques, probably brought from the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands, with the artistry of mestizo Guaraní women. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Jesuit missions promoted embroidery and lacework for religious and domestic uses.

Within that context, a distinctly Paraguayan version of European lace began to develop. This process of acculturation proved decisive: during Dr. José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia government and Paraguay’s subsequent isolation, local women, cut off from imported textiles, created their own handicrafts: ao po’i, encajeyú, and ñandutí among them. The city of Itauguá became the epicentre where the ñandutí was perfected, evolving from household craft into a national symbol.

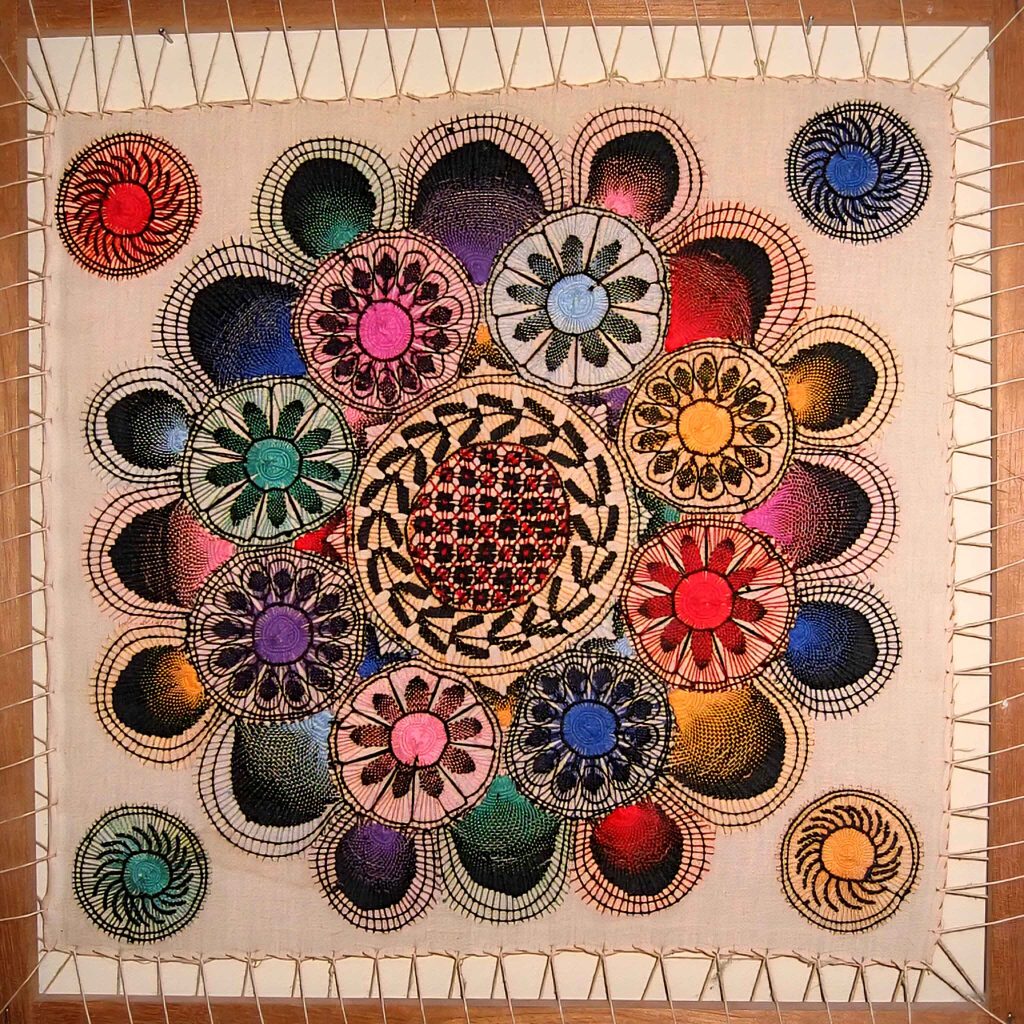

Unique characteristics

Ñandutí is woven on circular frames using fine white or brightly coloured threads. Its openwork designs emulate spider webs and feature both geometric and zoomorphic motifs. Common patterns include native flowers such as those of the guayabo and the mburukuja, making each piece truly one of a kind.

Traditionally used for religious ornaments, fans, hats, blouses and tablecloths, ñandutí today also adorns contemporary fashion, accessories, and export goods, maintaining its role as a proud expression of Paraguay’s artisan spirit.

Between history and legend

European travellers were already fascinated by Paraguay’s lacework in the early nineteenth century. In 1839, British brothers John and William Robertson recorded in their book Letters from Paraguay how, during a visit to Tapua’mí (now Mariano Roque Alonso), they were presented with an exceptional piece of ñandutí by Mrs. Juana de Esquivel.

The gift revealed how, by that time, Tenerife’s lace techniques had been fully transformed into a distinctly Paraguayan art: handmade by local women, prized for its refinement and fetching high prices.

The legend behind the lace

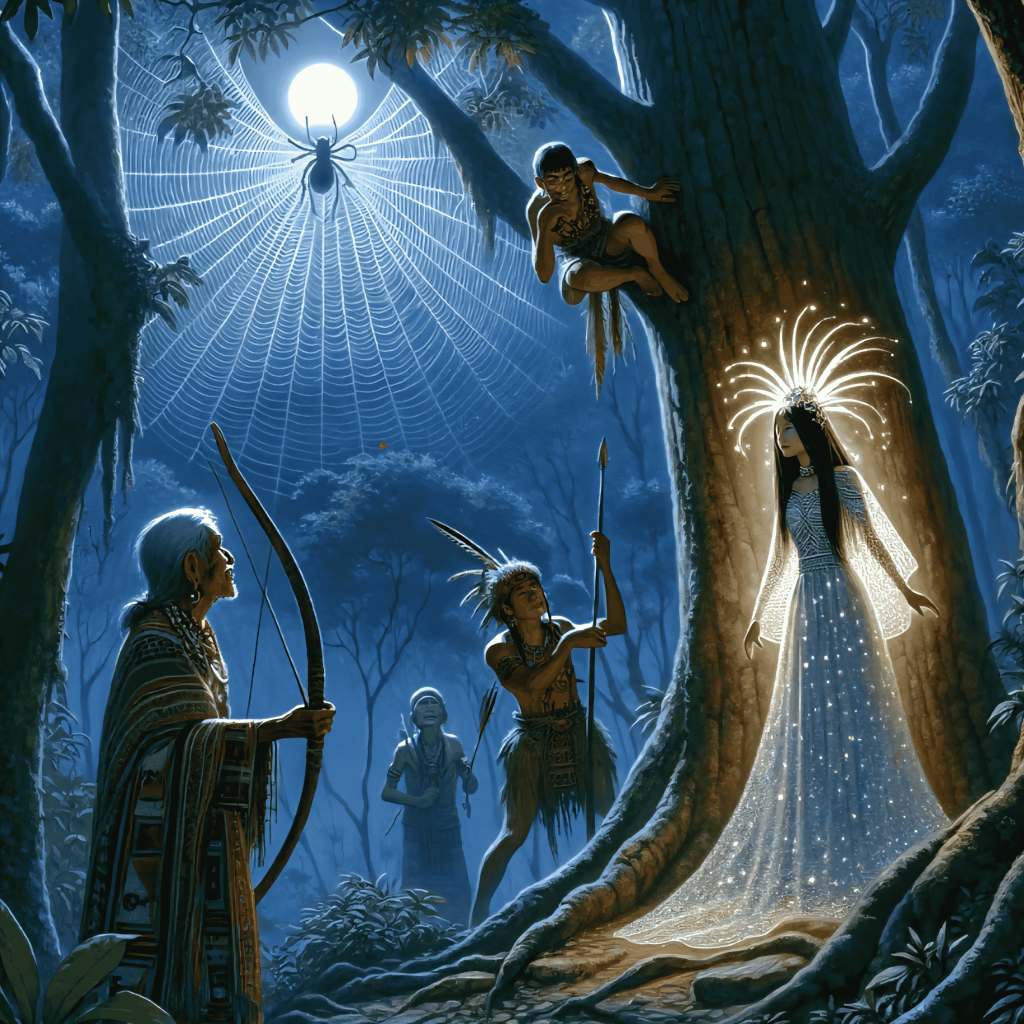

But history alone cannot explain the power of ñandutí without its legend. According to Guaraní tradition, Samimbi was the daughter of Guayra, the main cacique and spiritual leader of the Guaraní people. Guayra was fiercely protective of his beautiful, kind-hearted daughter, whose physique evoked a goddess and whose grace enchanted every young warrior.

He decreed that only a man who showed true originality and creative skills in gifts could win her heart. Mere strength or wealth would not suffice; ingenuity was the key to both his approval and his daughter’s affection.

Two warriors rose to the challenge: Jasy Ñemoñare (“son of the Moon”) and Ñandu Guasu (“the great spider”). One night, Jasy Ñemoñare spotted a shimmering silver lace atop a tree and sought to present it to Samimbi. Before he could climb down, however, Ñandu Guasu, seized by jealousy, killed him with an arrow. When he reached for the fabric himself, he discovered it was only a spider’s web and was overcome with remorse.

Ñandu Guasu’s mother, witnessing her son’s despair, studied the spiders’ craft and, with strands of her own white hair, recreated the lace to console him. This new textile amazed Guayra, who saw in it the originality he demanded, and thus Ñandu Guasu earned both his approval and Samimbi’s heart.

Other tellings alter the outcome. In one version, Ñandu Guasu spares Jasy Ñemoñare but still discovers the web dissolving in his hands, prompting him to tell his mother about the mysterious fabric. Another recounts the same events but calls the young woman Sapuru and describes Jasy Ñemoñare offering her bracelets of rare metals, shells and precious stones before dying tragically in the final duel for the spider’s web.

In each version, though, Ñandu Guasu’s mother weaves the first ñandutí and prays to Tupã, the almighty Guaraní god for blessings upon her son, and the craft becomes the inheritance of Samimbi’s and Ñandu Guasu’s descendants, a lineage said to carry the artistry into the present day.

Resilience and rebirth of Ñandutí Day

The War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870) nearly erased Itauguá and its artisans from the map. Yet one surviving weaver returned after the war and rekindled the tradition. Because of this resilience, ñandutí survived decades of upheaval and remains today an emblem of national identity.

Its importance is enshrined in law: Act No. 6105, officially established National Ñandutí Day, which is not merely lacework; but the expression of people who transformed adversity into art and mestizaje into beauty.

Each stitch tells a story of female endurance, communal creativity, and cultural continuity. In Itauguá, family workshops keep this heritage alive by teaching new generations both the technique and the legend. While these pieces now travel to museums and international catwalks, their essence still echoes the silver lace that, legend says, once shone beneath the moonlight and death.