Born on 27 August 1902, José Asunción Flores came into the world in the neighbourhood of La Chacarita, in Asunción. Despite his humble beginnings, the maestro, as cultural journalist Antonio Pecci (82) calls him, remains one of Paraguay’s most influential cultural figures`. His creation, the Guarania, turned one hundred years old in 2025. Yet, the details of his life and work remain little known, even among Paraguayans.

The genre is now an intangible heritage of humanity, thanks to UNESCO. To talk about the Guarania is to talk about José Asunción Flores. The Asunción Times recalls his story of artistic and cultural brilliance. Cultural journalist Pecci, who knew Flores personally, shares lesser-known facts about the maestro.

Early years

Born into a poor family, young Flores used to play in what is now the city centre of Asunción. He often accompanied his mother to the Big Market (Mercado Guazú), where Juan E. O’Leary and Democracy Plazas now stand. When he was eleven, following family problems, he ran away to Alto Paraguay and found work in a factory.

His mother eventually found him there, but José convinced her to stay and secured her a job at the same factory. According to Pecci, “José had a way with words that allowed him to convince anyone.” Soon after, his stepfather arrived, furious, and took them back to the capital. To discipline him, José was made to join the Police Band, located where the Police Command now stands in central Asunción.

He quickly stood out for his musical talent. True to his rebellious spirit, one day he asked one of his directors, an Italian, if they could play Paraguayan music. The director replied that “it did not exist; it was so simple that it was preferable to play any classical piece.” The maestro then began searching for that Guaraní expression that truly represented the Paraguayan in mind, body, and soul.

Birth of the Guarania

The first piece he composed was Jejuí, a response to that search for authentic Paraguayan expression. As a musical genre, the Guarania possesses unique qualities. As Pecci explains, “It is a genre without external influences; absolutely and completely homegrown.” Its creator is known, and he began performing it in 1925. This quickly catapulted him to fame in the capital. He was even praised by President Eligio Ayala during one of his concerts at a hotel in Asunción.

The Guarania differs from the more common Paraguayan polka because it is not meant for dancing. It is slower and deeply emotional. According to Pecci, “The Guarania was meant to be listened to, to reach the innermost fibres of the human soul.” These unique characteristics make it a singular genre in the world, distinct within Latin America.

Encouraged by fellow musicians, Flores met Manuel Ortiz Guerrero, a poet from Guairá. Their friendship would become one of the most significant in Paraguayan cultural history. Through Ortiz Guerrero, the Guarania evolved into a more melancholic form, not only in sound but in poetry.

The Guairá poet died in 1933 after years of illness. According to Pecci, on his deathbed he gave Flores the most important advice of his life. “Manuel changed the maestro’s life. He advised him to leave the bottle and the nights of partying, and to go to Buenos Aires, where he would gain everything he needed to become a true musician,” says Pecci. Flores would never drink again.

Composing abroad

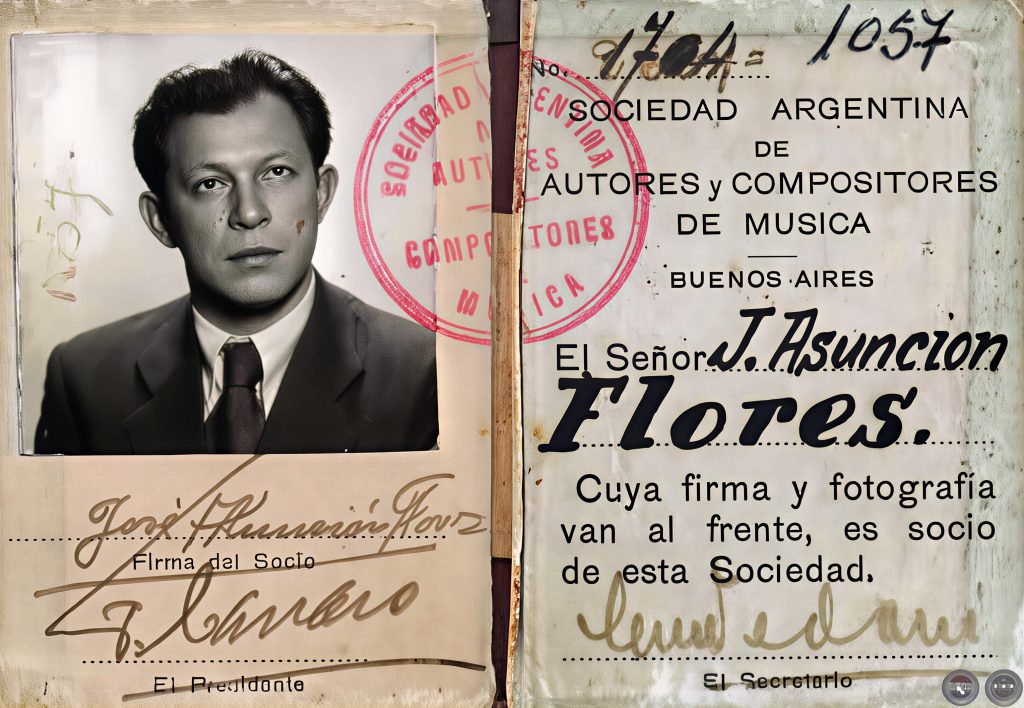

In Buenos Aires, Flores confirmed his musical genius and established himself as a true star, recording extensively throughout the 1930s. He became well known and respected by many Argentines. However, the political instability in his homeland made returning impossible.

By the end of the 1930s, for reasons not entirely clear, he stopped composing traditional Guaranias and began writing symphonies. His talent and fame even took him to Moscow.

As Pecci recalls, “He told us that the Russian maestros greatly admired his work and wanted to learn from him. He even sent us one of his recordings, which was broadcast on the only radio that played his music during the dictatorship.” Although Flores was not religious, he was friends with the director of that radio station, a Catholic priest. “But that was José Asunción Flores; he was a friendly and jovial man who had friends of every ideology and political background,” adds Pecci.

The fading of a star

Flores would never return to Paraguay. It was in Buenos Aires, around this time, that Pecci met him. Fellow countrymen would greet him warmly on the streets, and he always returned the greeting. “He did not usually know them, but it always filled him with joy to greet a Paraguayan. The Argentinians would call out ‘maestro!’, asking, ‘How are you?’ with their typical Buenos Aires accent,” Pecci explains.

“I was fortunate enough to meet the maestro, whom I had always wanted to see. I was lucky to become his friend, He was a great eater and often treated us to restaurants. He used to donate his allowances to charity. These qualities surely came from his humble origins. He had a great way with people and always wanted to spend time with Paraguayans.”

“He spoke his mind without hesitation”

José Asunción Flores died in 1972. However, when his remains were repatriated in 1991, crowds filled the streets to welcome him home.

“Perhaps what set him apart,” Pecci concludes, “was that he was never shy; he asked questions and spoke his mind without hesitation. He represents the artist fully devoted to his vocation, cultivated with care and sacrifice. Despite the recognition and success, he achieved both in Paraguay and abroad, he led a simple and humble life, never succumbing to vanity or pride. He was always conscious of his origins and remained true to his working-class background.”