Carlos Martini is a journalist of remarkable experience, an undisputed reference figure, and one of the most beloved communicators in Paraguay. He focuses on human stories with calm professionalism, avoiding sensationalism. This is part 2 of an interview with Martini, in which he speaks with The Asunción Times, presenting his most candid public persona. He often insists that what is seen on television is never the whole person.

A space of masks

“No one appears as they are,” he says. Media, in his view, is a space of masks. Authenticity is rare, perhaps uncomfortable, and often hidden from public view. To find Martini without performance, one must look elsewhere.

That place, he suggests, is not journalism, nor sociology, nor television. Literature, for him, remains the only territory without protection. “If you want to understand me, read my novels.”

A childhood marked by silence and refuge

Martini traces his intellectual life back to shyness rather than ambition. “I was very timid, very thin, and full of complexes.” When visitors arrived at his home, he would disappear. “I ran to my father’s library so they would not see me.” That library became a sanctuary. “There, I found peace. I found refuge.”

He insists that journalism came much later. “If you ask me what in my childhood led me to journalism, the answer is nothing. First, I was a reader. Only afterwards did I become a sociologist, and later, a journalist.”

Literature as truth without protection

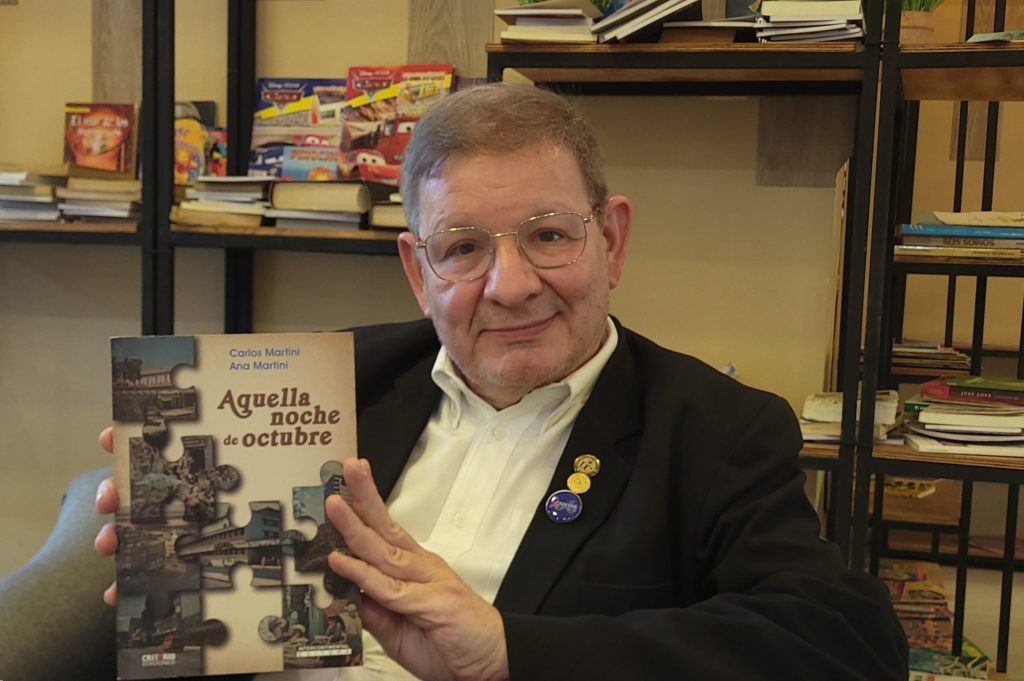

Martini is clear about where he can be found without masks: “In my literature.” Journalism and sociology, he insists, demand distance; literature does not. He refers to the idea of the “truth of lies”, the notion that fiction invents worlds in order to reveal deeper truths. “There you are, who you are,” he explains. Exposure, not comfort, is literature’s true function. Martini has published several stories, including An April Afternoon, That October Night, and Where Is My Spring?.

Mental health as lived knowledge

Martini speaks about mental health without euphemism. “We are a sick society,” he says bluntly. He believes depression, anxiety, and stress mark an entire generation.

This concern is deeply personal. In 2015, his mother developed Alzheimer’s disease. Martini lived with her. “My entire world fell apart.” He entered a severe depression and required years of psychological treatment. “It took me at least three years to recover.” Since then, he says, mental health has become an essential part of his work and reflection.

Martini also speaks with admiration about Gustavo Alfaro, the Argentine football coach. “He speaks like a philosopher.” What interests him is not tactics or results. It is the way Alfaro understands life.

Martini admits a personal wish. “My dream is to interview him.” Not about formations or championships. He wants to ask about meaning. “About why he speaks the way he does.”

Paraguay, identity, and the limits of definition

When asked about Paraguayan identity, Martini resists simplification. “It does not exist.” He questions the idea of a single national character and points to deep social fractures that prevent a shared experience.

Despite his scepticism about identity, Martini firmly believes in culture. Literature, music, theatre, and visual arts, he argues, express what society cannot easily articulate. He highlights Paraguayan music, especially the guarania, as a truthful emotional register.

If asked to introduce Paraguay to a newcomer, Martini would recommend books rather than slogans or statistics. Titles such as La libreta de almacén by Mario Halley Mora, La niña que perdí en el circo by Raquel Zaguier, and La babosa by Gabriel Casaccia “because Casaccia portrays Paraguay as it truly is, not as we like to claim it is,” are essential starting points. He also highlights Hijo de hombre by Augusto Roa Bastos as indispensable for understanding Paraguay. Literature, he believes, reveals what numbers never can.

The sadness that shapes his reading

Martini openly admits his preference for difficult literature. “I do not read to be entertained. I want books that strike the heart.”

He believes sadness reveals more than happiness. Joy, in his view, is fleeting. “Moments of joy are enough.” Pain, by contrast, leaves deeper traces. He cites writers such as Franz Kafka and Alejandra Pizarnik, who transformed despair into art.

When asked what remains unsaid about him, Martini answers carefully. “A lot. Human beings are defined by what they hide.” Full transparency, he argues, is impossible. That impossibility is precisely why fiction matters. “In fiction, one passes reality through imagination. By lying, literature tells the truth. It reveals what cannot be stated directly.”

Solitude, animals, and chosen distance

Martini describes himself as radically solitary. “I do not enjoy human conversation.” Silence restores him; social interaction exhausts him.

There is one exception. His dog, Bobby. “With him, I am myself.” He speaks to him, plays with him, and sleeps beside him. The relationship, he suggests, is uncomplicated. “A single gesture from him gives me more peace than many therapy sessions.”

Martini insists that the viral version of himself is not real. “That is not me,” he says of televised dances and light moments. Those belong to television logic.

He quotes Ernesto Sábato: “We all wear masks.” Except, he adds, in solitude. “When one removes the masks, it is terrifying.” That confrontation, he believes, is unavoidable.

A final word on reading and freedom

When asked for a message to readers, Martini returns to reading. “Read obsessively, but with freedom.” He rejects obligation and literary authority.

“If a book does not speak to you, leave it,” he advises. Follow curiosity. “There is nothing more personal than choosing a book.” For Martini, reading remains an act of autonomy. A quiet rebellion. And, perhaps, a way of staying true to himself.

This article was written in collaboration with Juanfer, another author from The Asunción Times.