Every December 8, Paraguay stops to pay homage to the Virgin of Caacupé, one of the most venerated religious figures in the country. This festivity, in addition to being an expression of faith, is a bridge to the values, history and culture that have defined our society throughout time. In an exclusive conversation with historian Claudio Velázquez, we unravel the most fascinating and profound aspects of this tradition that transcends generations.

The old temple and cultural heritage of the Virgin of Caacupé

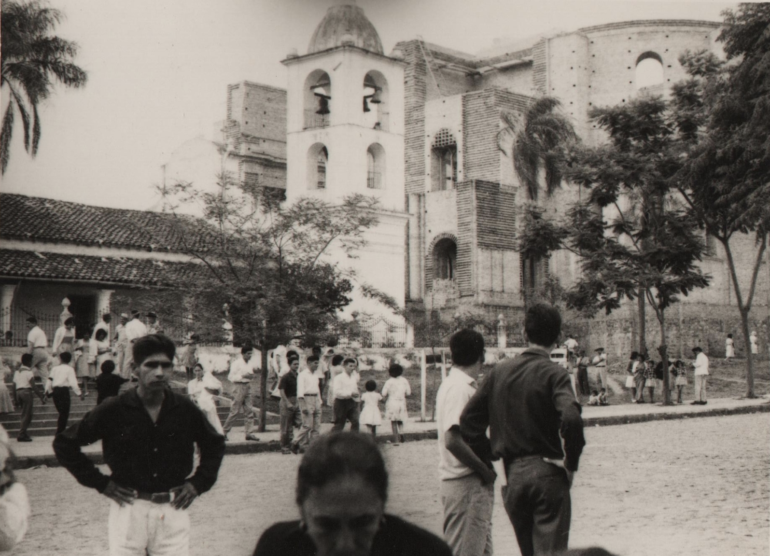

The devotion to the Virgin of Caacupé has a close link with its temple, whose history dates back to the 19th century. According to Velázquez, the first temple, built in 1808, was struck by lightning, which seriously damaged its structure. It was during the government of Bernardino Caballero, in 1879, when the construction of a new building known as the “old church” was authorized.

“If we ask our parents, they might even tell us that they have seen and even entered the old temple, where the esplanade is now. Unfortunately, it could not stand and ended up collapsing. A replica of this temple was made in Tupãsy Ykua , even some of its materials were used, but it is nothing more than a replica. I think that this should teach us to value what cultural heritage is, regardless of whether we focus on new constructions or projections,” emphasized Velázquez.

“The first known event, where people were reported making a pilgrimage to Caacupé, occurred in 1875.”

The Caacupé festival evolved, consolidating itself as a pillar of national identity. Over the years, the Virgin was present at crucial moments in Paraguayan history. Velázquez highlights how this devotion gained strength after the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870), when Father Fidel Maíz spread the legend of the Indian José, a key figure in Guaraní mythology and a symbol of divine protection.

“The Paraguayan people needed unity and devotion to the Virgin to believe in a reconstruction process and gain strength. And that is where the Virgin of Caacupé comes into play”, explained the historian. He also added: “The festivity evolved throughout the history of Paraguay through different key episodes. An example is the Chaco War, a period in which many of the combatants who went to war entrusted themselves to the Virgin to return home safe and sound. That is why the project to build the new basilica was born in 1940, some time after the conflict”.

Velázquez also addressed a lesser-known episode, but one of great historical relevance: the decision of Bishop Ismael Rolón to suspend the procession of the Virgin in 1969, during the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner. “As a result of the political persecutions that were taking place during the Stroessner dictatorship, Rolón made the decision to suspend the traditional procession that year. At that time, it was already a tradition to make a tour of the town of Caacupé with the image of the Virgin, and in that year he made the decision to suspend this act. It was only referred to the mass, and this procession was always accompanied by Stroessner. It was one of the first acts of protest against the persecutions that occurred during the period of the dictatorship. Later, he became Archbishop of Asunción and had an important history of confrontations with the dictatorship,” he said.

“During the Chaco War, a period in which many of the combatants who went to war, entrusted themselves to the Virgin to return home safe and sound.”

The tradition of pilgrimage to the Virgin of Caacupé

The pilgrimage to Caacupé is one of the most moving expressions of Paraguayan devotion. Velázquez describes how, since the 19th century, the faithful have found ways to manifest their faith: “The pilgrimage has always had its own particularity. People went in their carts, what’s more, even when it was under construction, which was for a very long time, it is remembered that the people who went on pilgrimage carried a stone on that journey, which could later possibly serve or be used in that process of building the new temple.”

The historian also mentions that the first records of pilgrimages date back to 1875, in a context marked by political tensions, such as the revolutionary uprising against President Juan Bautista Gill. “The first event that we have, where people are reported making a pilgrimage to Caacupé, occurred in 1875, when a revolutionary uprising occurred in Paraguay during the presidency of Juan Bautista Gill, and this revolution sought to take advantage of the fact that people, in a certain way, were going to make a pilgrimage to Caacupé,” he said.

One element highlighted by Velázquez is the link between the Virgin and the Guaraní traditions. “During this evangelising process, this town was founded in 1769. It was directed to what was the first chapel based on an image that was donated by the Church of the town of Tobatí. This process that is taking place in different towns is key. And, above all, also the legend of the Indian José, which although it is a legend, is something that comes to us today. It is perhaps one of the strongest and best known within Paraguayan culture,” he explained.

Beyond Faith: Lessons for the Present

Velázquez concludes with a reflection on the importance of preserving cultural and religious heritage: “My perspective is that the tradition of pilgrimage to Caacupé persists because of the very religiosity of Paraguayan society. Because society finds strength and hope in that religiosity, in that devotion to the Virgin, and it is something so important that, fortunately, it persists in society and allows this culture to be maintained.”

The Day of the Virgin of Caacupé is a reminder of the values that unite the Paraguayan people. From the historical episodes that shaped the nation to the unwavering devotion that drives pilgrims, this holiday is, without a doubt, a cultural treasure that deserves to be celebrated and preserved.