In the sweltering heat of the Paraguayan summer, early February 1989 felt different. For over three decades, the country had existed under the frozen shadow of General Alfredo Stroessner. By the time the “Sun of Mexico,” nineteen-year-old Luis Miguel, touched down for his legendary concert in the city of Itá, the atmosphere had changed. The air was not just thick with humidity; it was heavy with the scent of an ending.

A surreal stage

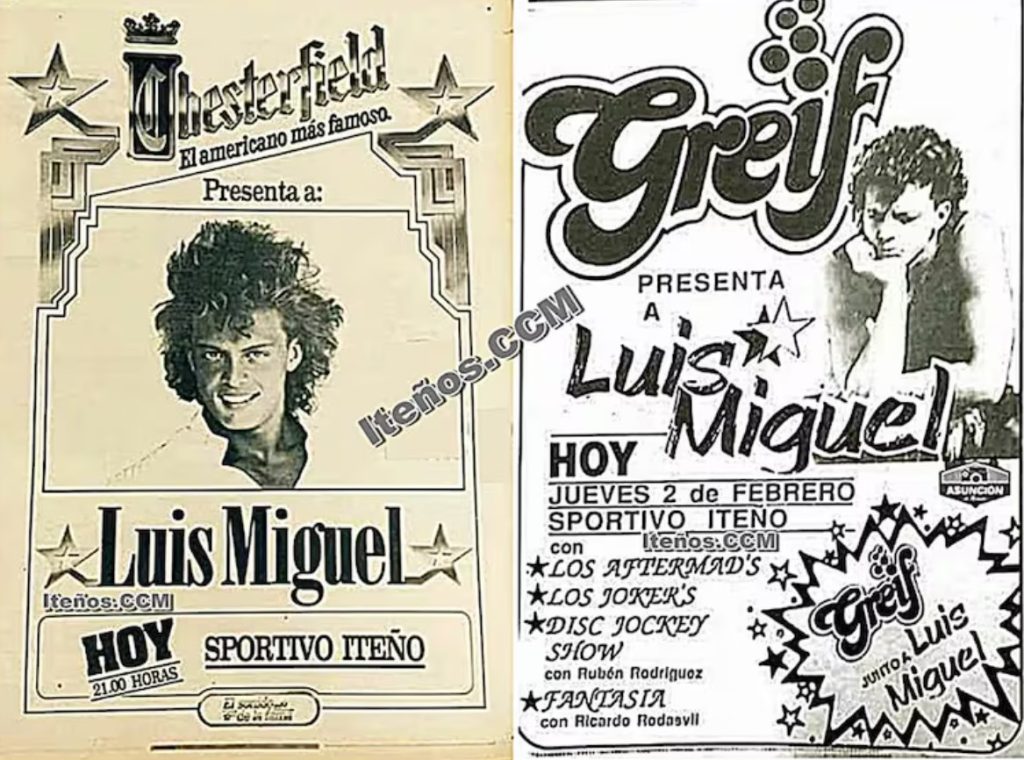

Itá, a town known more for its artisanal pottery than international spectacles, became the unlikely epicentre of a cultural earthquake. The venue was the Sportivo Iteño stadium. While the regime prided itself on “Peace and Progress,” the infrastructure told a different story. The concert was a logistical anomaly; a flash of high-production sequins and synthesisers dropped into a landscape of red earth and simmering political tension.

Luis Miguel was at the absolute zenith of his early career. Dressed in oversized blazers with hair that defied gravity, he represented a modern, cosmopolitan world that many young Paraguayans felt locked away from. For the fans screaming to La Incondicional, the concert was an escape. For the authorities, it was perhaps a distraction they could no longer control.

Source: Iteños.ccm

Sergio Denis and the announcement that shook a stadium

As the opening chords rang out in Itá, the “Stronismo” era was physically dismantling itself just a few kilometres away in the capital. While the youth was lost in the romanticism of the music, the upper echelons of the military were finalising the details of Coup d’État.

The bubble of pop-fuelled escapism burst in the most dramatic fashion imaginable. The late Argentine singer Sergio Denis was also performing in Itá, at a stadium near the one of Luis Miguel. He took to the microphone not to introduce a song, but to bridge the gap between the stage and the reality unfolding in the streets.

A military movement underway in Asunción

With a gravity that silenced the stadium, Denis informed the thousands gathered that a military movement was underway in Asunción. He congratulated the Paraguayan people to have regained liberty. The atmosphere shifted instantly. In an era before mobile phones, this was the first many had heard of the uprising.

On Luis Miguel side, it was completely different. Considering the popularity and the power of attraction of the singer, nobody told him, and so the crowd was not aware. As per the presentator that night, Rubén “El Pionero” Rodríguez, and the journalist Juan Riveros, the military did came around the third song, “La Chica en el Bikini Azul”, to try to stop the show. The military had no success and the show continues as if nothing had happened. The irony was stark: while Denis and Luis Miguel sang of longing, the heavy artillery was beginning to roar.

The backdrop of a coup

The contrast was cinematic:

- Inside the stadium: The choreographed perfection of a pop idol and the collective joy of a generation hungry for change.

- In the barracks: The clinking of heavy weaponry and the hushed whispers of General Andrés Rodríguez’s inner circle.

There is a local legend that suggests the sheer volume of the crowds and the chaos of the event provided a strange sort of cover. While the secret police were traditionally everywhere, that night, their attention was fractured. The regime’s grip was slipping, loosened by the very modernity they tried to curate.

Parents looked for their children, and the wealthy elite – many tied to the Stroessner apparatus – began a frantic exodus toward their vehicles as the “Sun of Mexico” performed against a backdrop of impending war.

The morning after Luis Miguel’s concert

Luis Miguel left Paraguay – safely. While there are many legends and versions of the story about how he got out of this conundrum (hotel in Guarambaré, living in a someone’s home in Itá, and many more.), he did leave the country safe and sound.

He left behind a country that was fundamentally altered. On the nights of February 2nd and 3rd of 1989, the tanks finally rolled. General Alfredo Stroessner, the man who had ruled Paraguay since 1954 was ousted in a violent coup d’état. This was bringing a definitive end to the longest dictatorship in South American history.

The concert in Itá remains a vivid memory – not just for the music, but for the “before and after” it represents. This Luis Miguel concert was the last great event of the Old World. When the sun rose after that weekend, the “Sun of Mexico” was gone. The long-awaited dawn of Paraguayan democracy had finally, albeit messily, begun. The Golpe de la Candelaria gave new hope to the concert-goers.