Paraguay’s currency tells a story beyond its value. In the weekly series “Money Talks”, The Asunción Times takes readers on a journey through the nation’s Guaraní banknotes. Each edition will explore a different bill, revealing the history, culture, and notable figures depicted on it. The series will also highlight the hidden details that make each note unique. From pioneers of education to national symbols, this series uncovers the stories woven into Paraguay’s money.

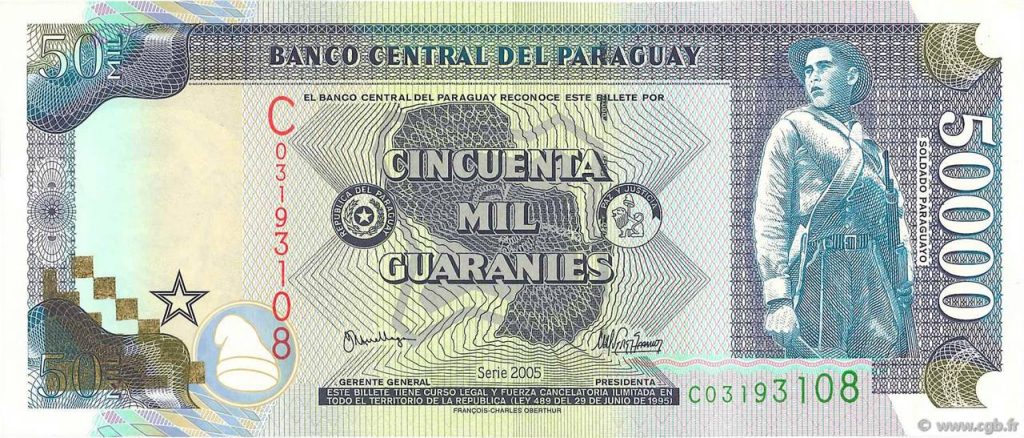

Following our look into the iconic mix-up on the Gs. 2,000 banknote, the hidden features of the Gs. 5,000 note, the disputed iconographic mistake of the Gs. 10,000 note, and the artistic legacy of the Gs. 20,000 guaraní note, this week we have the three stories behind the 4 versions of the 50,000 Guaraní banknote.

“El Soldadito”

The fifty-thousand-guaraní banknote, once widely known among Paraguayans as “El Soldadito” (“The Little Soldier”), has carried with it peculiar stories since its very beginning. Originally, the bank note featured the face of former President and Dictator Alfredo Stroessner. Later, the bill bore the image of the Paraguayan Soldier. And now, the bank note displays the portrait of Paraguayan musician Agustín Pío Barrios, “Mangoré”, after following a series of incidents.

Evolution of the 50,000 guaraní banknote

The first design of the 50,000 banknote depicted the face of Paraguay’s former President Alfredo Stroessner. In 1978, a banknote bearing Stroessner’s portrait was about to enter circulation. However, the reason it was ultimately rejected remains unknown. Interestingly, the Central Bank of Paraguay still has the two samples available at its headquarters. According to those close to the former president, Stroessner did not see himself as a monarch. Therefore, he thought it was inappropriate for his face to appear on a banknote. Nevertheless, he allowed coins, stamps, and medals featuring his effigy.

That design showed the former president on the front and the Acaray II dam, part of the National Electricity Administration (ANDE), on the reverse.

It was not until 1993 that the 50,000-guaraní banknote was officially issued, fifteen years after the first draft. The 1993 design featured the Paraguayan Soldier on the front and the House of Independence on the back. The main design on the front depicted the Paraguayan Soldier, a combatant from the Chaco War, positioned slightly to the right. In the centre appeared a map of Paraguay, flanked by national coats of arms on each side.

In the lower left corner was the Phrygian cap, symbol of liberty. These banknotes were printed on 100% pure cotton paper, new and clean.

Theft and changes

The Series A and B banknotes of 50,000 guaraníes remained in circulation until an event forced a drastic change. A theft suffered at the Central Bank of Paraguay during the presidency of Mónica Pérez. Mónica revealed the Series C banknotes had disappeared in the port of Montevideo while being shipped from France to Paraguay. The loss amounted to around US$2.5 million in guaraní notes. In the following months, some of the stolen Series C notes began appearing in Paraguayan cities such as Pedro Juan Caballero, among others.

In 2008, the Central Bank of Paraguay introduced a new design for the fifty-thousand-guaraní banknote. The design was entirely different: more colourful and vibrant. Replacing the image of the Paraguayan Soldier with that of Agustín Pío Barrios, better known as “Mangoré.” This radical redesign aimed to prevent confusion with the stolen Series C notes, whose appearance closely resembled previous issues, allowing counterfeiters to deceive the public.

The new 50,000 Guaraní banknote

The new banknote features the portrait of the renowned Paraguayan guitarist Agustín Pío Barrios, a small map of Paraguay, and part of a guitar. The colour palette includes lilac, light and dark green, soft orange, and sky blue.

On the reverse, new security features were added to prevent forgery. Ultraviolet light reveals a musical staff on the right-hand side. The face of Mangoré and the guitar reappear, along with the denomination written in Guaraní (popasu guaraní), the traditional ñandutí lace, and other details.

Initially, the Mangoré notes circulated alongside the Soldier notes. From 4 October 2008, the Central Bank opened a three-year period for the complete withdrawal of the old design. Holders of Series A and B (1997 and 1998) notes could exchange them for the new “Mangoré” issue until October 2012. After that date, even the Central Bank would no longer accept them.

Who was Mangoré?

Mangoré was born in San Juan Bautista, in the Misiones Department of Paraguay. He came from a large, musically inclined family. Each of his siblings played an instrument, forming the Barrios Orchestra. His father, Doroteo Barrios, was an Argentine consul in Misiones, while his mother, Martina Ferreira, was the headmistress of the girls’ school in Villa Florida. After graduating from the Colegio Nacional de la Capital, he began performing concerts and composing.

On 14 August 1932, in Bahia, Brazil, he appeared as Nitsuga Mangoré — the Paganini of the Guitar from the Forests of Paraguay. “Nitsuga” is Agustín spelt backwards, and “Mangoré” comes from a legendary Guaraní chief who died for love. He not only adopted the name but also performed in traditional Paraguayan attire.

The character of Mangoré became so popular that people in several countries knew him better by that name, than by his own.

Mangoré’s legacy lives on

Today, Mangoré’s legacy continues through Berta Rojas, Paraguay’s most celebrated classical guitarist. She has dedicated much of her career to rescuing and reinterpreting his music, recording albums such as Intimate Barrios. In 2011, she launched the international tour “Tras las Huellas de Mangoré” (“In the Footsteps of Mangoré”) alongside Paquito D’Rivera as guest star. A four-year journey retracing the steps of Agustín Barrios across the Americas.

Thanks to Berta Rojas, the name of Barrios Mangoré has reached new generations. His work endures in concert halls, academic recordings, and educational projects. Both artists embody the perfect union between artistic excellence and Paraguayan identity.